Fandom and textual poaching are two interesting concepts that are growing year upon year and season upon season of almost every popular modern television programme. Given advances in technology it is almost impossible to avoid being a part of these concepts, especially if you’re a television lover of a younger generation. It is fascinating to think of how television led to these two consumer concepts booming and having as big of an impact on the media as well as the TV programmes themselves. A popular show with many series’ that can be applied to both fandom and textual poaching is Brooklyn Nine-Nine. This show grabs the attention as the fan base is obviously particularly passionate about the programme and being an avid viewer myself it’s evident as to why. This piece will be exploring strengths and limitations of the two outlined concepts as well as how they apply to Brooklyn Nine-Nine and the extent of this. It will also discuss how the consumers, including myself, fit into each category and what impact this has on social media and the show itself.

Fandom is a common aspect of popular culture in the modern society of all forms of media. It chooses from the range of “mass-distributed entertainment” and takes it into the “culture of a self-selected fraction of the people” (Fiske, 1992). By definition fandom is the state of being a fan of someone or something, in which can branch out into music, sport or indeed any part of the media. I will be focusing on fandom in Television. It has to be said that a limitation could be argued of fandom as there is no real criteria to meet that would place a consumer in the ‘fan’ bracket and therefore there is potentially no such thing as fandom. Seeing as “there are no real distinctions that mark the ‘fan’” (Grossberg, 1992), it could be seen by many as a perceived status and therefore it has no impact on the media. This argument can be strengthened by the thought that “everyone has a fandom” (Rogers-Whitehead, 2016) and if everyone adores “that one TV show; you just can’t wait until the next season comes out” (Rogers-Whitehead, 2016), then is fandom up in the air as a concept and does that put every consumer in the same group. If this was the case, it would mean fandom is very one dimensional as a theory and would possibly eliminate all concepts that lead on from it, such as: textual poaching and participatory culture.

On the other hand, fandom has been argued in more recent times to have great positive impacts on the television industry as well as a range of social media platforms. Due to the growing influence of “consumers as producers” (Gauntlett, 2008) it has become evident that fandom is having increasing “economic and promotional value to content producers” (Coppa, 2014). Consumers’ growing power is extremely significant on the most popular social media platforms, such as YouTube and Twitter, which include trending pages to display what is popular doing well in the media. This immediately attracts other users that haven’t learnt or experienced the item that is trending to be involved as soon as possible so they don’t miss out on what’s ‘trendy.’ Therefore a producer with very little power or status can suddenly be all over the media solely down to the influence of consumers. This is because advances in technology make it so easy to view, like or share a piece of media and this boost to the producer’s media coverage has strong economic implications as well.

As mentioned this is made possible by concepts that develop from fandom, such as: participatory culture and textual poaching. These theories are all interdependent however; I will be focusing on textual poaching as a result of fandom. Textual poaching is a term coined by Henry Jenkins (1992) and can be classified as the process by which dedicated fans respond to popular media. This, in layman’s terms, is fans taking their favourite pieces of media and being creative with them to create new pieces of media. This leads to a broad variety of fresh media and can be anything from: “commentary and close reading, stories and poems, songs and videos, re-enactments and animations and mash-ups, screen shots and icons” (De Kosnik, 2012). Working as a perfect promotional resource, it increases viewership for TV programmes and indicates to producers any improvements to make or whether to release a new season of the show. As a result, the producer of the television programme can increase revenue from a new season and perhaps expand their economies of scale given the increased viewership that has been gained from other platforms.

Conversely, textual poaching has its disbelievers and has been criticised along with fandom for not offering anything to the industry itself or other forms of media. It’s been argued to “disparage fans as prolific amateurs” (De Kosnik 2012) when creating their tributes to the TV shows or other media that they are fans of. People with this opinion would believe that the fandom and new media created surrounding a television programme adds nothing to the industry and can go as far as thinking fans hinder it. Some textual poaching can have an adverse effect to the promotional benefits where memes, gifs or parodies can be seen to mock the television programme. This can even occur through fandom as previous fans could be very disappointed or angry at a path the television show has taken.

The TV series that I will be later applying these two theories to is E4 and NBC’s Brooklyn Nine-Nine. This police procedural sitcom is a comical take on the life of American police and investigators that first aired on 17th September 2013. The Golden Globe-winning sitcom was originally aired on Fox (USA) and subsequently moved to NBC (series 5 and 6) as well as being aired in the UK on Channel 4’s E4. It has also become cross-platform and has taken Video on Demand (VOD) by storm since its launch on Netflix and Hulu. There have also been box sets of the series released as fans want to experience their moments again. Its 6 seasons have been extremely popular in both the UK and USA with its most recent episode coming it at the 23rd most viewed programme of the week for adults aged 16-24 with a total number of views at 144,000 (BARB, 2019). Furthermore, the season 6 premiere was viewed by 3.6 million people aged 18-49 (Entertainment Weekly 2019). The fact that Brooklyn Nine-Nine has such a strong, passionate fan base means that it’s a show with a lot of fandom and therefore thousands of examples of textual poaching. Thus, it is an absorbing discussion as to the extent of textual poaching and fandom surrounding the TV series and how this impacts the industry and social media.

There are several elements of television that don’t just attract a large viewership but also lead to high levels of fandom. For example, Brooklyn Nine-Nine possesses a very catchy theme tune in which fans can immediately bond over and link to their favourite show. Alongside this, there are many routines or common factors that occur in each and every episode that create a basis for fans to make jokes from. This includes certain features of the main characters, such as: Captain Holt’s expressionless face, Jake Peralta always being late and Gina Linetti’s constant arrogance. These and other familiar moments of the show have created a whole world of inside jokes for Brooklyn Nine-Nine fans to share and create. This perhaps is the likely reason for so many Brooklyn Nine-Nine fan pages on social media platforms. These primarily include Twitter and Tumblr but due to the three main female characteers being predominant in the narrative, it has also seen popularity on female fan fanwork exchanges, such as rarewomen. The viewership and fandom is further increased due to it being a cross-platform show. This means it can be viewed by more consumers as it’s “an intellectual property, service or story or experience that is distributed across multiple media platforms” (Ibrus & Scolari 2012).

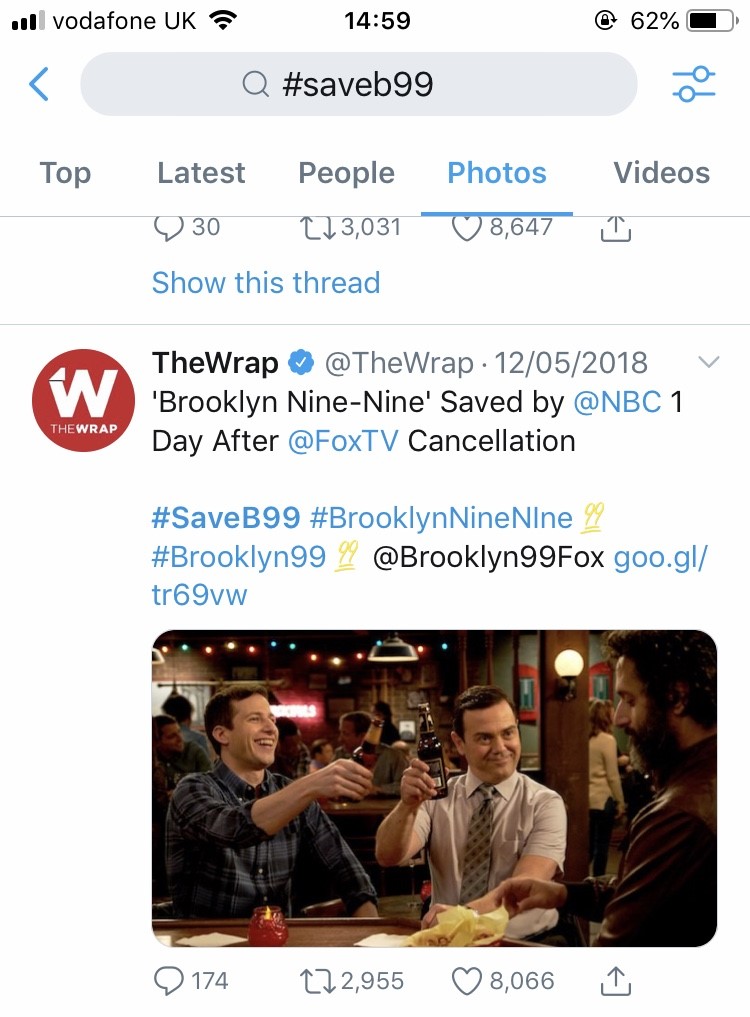

Fandom for this show in particular has been absolutely crucial not just for the success of it but to keep it alive. In May 2018 original broadcasters of the show Fox decided to cancel the programme altogether leaving Brooklyn Nine-Nine fans distraught with the decision. This led to uproar on social media with thousands voicing their opinion and the former Fox TV show climbed high the trending charts. Fans of the show led the protests with Twitter hashtags that caught on extremely quickly. These were: #RenewB99 and #SaveB99. Their fandom shown through loyalty for show was also demonstrated by the nickname of ‘B99’ that brings the group of consumers together. This hashtag was used with accompanying Gif’s and memes taken from parts of the show and other pieces of media to express their feelings. Additional petitions were signed by thousands with the focal one reaching 39,492 supporters. The campaign was successful as the fans of Brooklyn Nine-Nine saw their favourite TV programme picked up by new broadcasters NBC within 31 hours of Fox’s cancellation announcement. It could be strongly argued that the television show was almost entirely resurrected by fandom and the slight incorporation of textual poaching. NBC since has gone on to broadcast series 6 of the American sitcom and are set to release a 7th. Fans continued this activity after the show was picked up to show their support. The fandom in this case has thus been a major success for Brooklyn Nine-Nine and certainly hasn’t hindered the show in any way for this example.

For the fans this is crucial not just so they can continue to enjoy their favourite show but so they can also carry on their social involvement in the show. It is an important part of everyday life for fans of anything, including television, as “it impacts upon how we form emotional bonds with ourselves and others” (Williams, 2015). Therefore, it isn’t simply a fictional world for them as it spills over into their real life and becomes a part of their wellbeing. As part of a fandom, these specific types of consumer don’t just watch Brooklyn Nine-Nine for “entertainment” purposes, although that would’ve been the initial attraction but for “integration and social interaction” (Blumler & Katz 1974). It is to consume a media text knowing you’re going to discuss it on social media or the next time you see friends and can be as significant as playing a role in making friends. Brooklyn Nine-Nine can be argued to form a community feeling within its fandom by creating an inclusive feeling and a common ground for conversation.

Fandom and textual poaching therefore go hand in hand as this community of especially loyal consumers spend a lot of their time discussing Brooklyn Nine-Nine on social media. The fan pages, as previously displayed act as a hub for the community to gather in to share their thoughts on the series or the most recent episode. This can be at any time but on Twitter will usually happen live through the use of hashtags, Gif’s and memes. The fans “create a variety of new analytical and creative works” (Tosenberger, 2011) based around their favourite show. This very much integrates the idea of “consumers as producers” (Gauntlet, 2008) and can also have a strong effect on the industry as well as the social media following. For example, the way fans react to a certain outcome of an episode can encourage the actual producers to take their opinions on board for future narrative twists.

Furthermore, these fans have taken “a creative step to make the words and characters their own” (Jenkins, 1992). This has been done through memes of Brooklyn Nine-Nine that take original images or videos from the TV series along with words from the original script but insert them into a new context to give them a fresh interpretation of the meaning. Although it could be argued that this offers nothing for the actual show itself, it could certainly act as something with good “promotional value” (Coppa 2014) for the TV programme as almost every young person is on social media. Approximately 67% of the UK population (Avocado Social, 2019) and 69% (88% 18-29 years old) of the USA (Hootsuite, 2019) have at least one social media account. Consequently this would extend the viewership simply through fans discussing it and attracting attention of others. Here are some examples provided.

The fans conduct their textual poaching by “operating outside of the industry’s paradigms” (Tosenberger 2011) by which almost creates a whole new genre and distribution of the TV programme’s brand/identity. This can be seen by the YouTube reviews, Twitter memes or Facebook Gif’s being a completely different type of media, genre and experience to that of an actual episode of Brooklyn Nine-Nine. “YouTube has become an emblem of participatory culture” (Shifman, 2012) due to textual poachers using it to analyse their favourite TV programmes. Due to the theme of “whimsical content” (Shifman, 2012), it gives fans the opportunity to bond and have fun with other fans to encapsulate the idea of fandom through textual poaching. Prior to the collapse of Twitter’s Vine in October 2016, videos titles similar to: ‘Brooklyn Nine-Nine as vine’ were an extremely popular way of adapting the context of the show. This would include 6 second videos that Vine users had made, unrelated to Brooklyn Nine-Nine, that fans of the show would label as actions of characters from the programme. Despite Vine uploads being disabled, many of compilation videos are still circulating on YouTube as the fandom of the show is very powerful. Furthermore, ‘memes’ of Brooklyn Nine-Nine are still very popular on social media platforms, such as: Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. These are usually still images or short videos from the show with a new piece of text added to modify the meaning in a humorous manner. On the contrary, they can be images or videos from another media text and have added text that references Brooklyn Nine-Nine itself. This is particularly effective for the sitcom due to the many inside jokes that run throughout each series as previously stated. This demonstrates how fans have “become active participants in the construction and circulation of textual meanings” (Jenkins, 1992), in which could certainly be argued as a positive for the show’s producers and broadcasters as it immediately promotes the show as popular and comical.

In contrast, there are more serious social media videos that are evidence of fandom. YouTube reviews of virtually everything exist and that is no different for television programmes. These reviews stem from fandom as it is usually the most knowledgeable and passionate fans that that pick apart the show. For the majority of these video, there is only praise and it’s recommended that other people who haven’t seen it become a fan.

Further crossmedia examples of Brooklyn Nine-Nine’s fandom and textual poaching working in tandem are the show’s official website and the character soundboard. The soundboard could be argued as an example of textual poaching as it is content taken from actual episodes and taken out of context for an entertainment purpose. This and the official website display a sense of fandom as consumers are passionate enough to research and be submerged in their favourite programme on other media platforms.

Previously to this research I would’ve definitely put myself in the fandom bracket for Brooklyn Nine-Nine. I would’ve judged this on my passion for the show the feeling I get when I watch it and my anticipation levels for each and every new episode or season. However, the research has indicated that it is perhaps a very grey area as to whether someone is experiencing fandom or whether they’re just a regular consumer. After discovering that fandom is potentially deeper than just labelling yourself a fan, I would still place myself in the fandom segment of Brooklyn Nine-Nine consumers. This is because my involvement with the show isn’t limited to simply the television, which is E4 in the UK, but it expands to a crossmedia/cross-platform scale. For example I have liked both the official and fan pages for Brooklyn Nine-Nine on Facebook and regularly keep up to date with the popular hashtags surrounding the programme on Twitter. It has also come to my attention that fandom could simply be a concept relying on perception of self-status in which case I would still consider myself a real fan as that is the group of consumers that I would’ve already placed myself in.

However, the idea that it could be a grey area has more of an impact on my new opinions of the fandom theory. This is that fandom isn’t a strong concept or a strong influencer given that “everyone has a fandom” (Rogers-Whitehead, 2016) of sorts so consequently every consumer has the same opportunity to impact the television industry or social media for whatever show their passion is located within. My research on fandom will not change my future involvement within the theory for Brooklyn Nine-Nine however; I will consider what is classed as fandom differently as I agree with the notion of perception of self-status being the key drive for fandom groups.

Textual poaching, on the other hand, is something that my involvement may change in for the future. My research has led me to believe that, despite some opinions within the television community, textual poaching and participatory culture are both positive for the industry. For example, all positive reviews, funny memes or comical vines based on Brooklyn Nine-Nine do nothing but benefit social media and the actual show itself. They act as an extremely good promotional tool with no cost at all for the producers or broadcasters of the show. Contrarily, any negative reviews or opinions shared through the social media through textual poaching act as a basis for Brooklyn Nine-Nine to be improved for every episode and every season. These also give good information for potential consumers who haven’t watched the programme before and being a consumer myself, reviews of any nature are always useful. Therefore, as someone who was a fan of Brooklyn Nine-Nine but stayed away from textual poaching, I could likely take part in something creative like this in the future to both support my favourite show and to be included in the social interactions between fellow fans.

My research has allowed me to draw upon multiple conclusions about fandom and textual poaching within Brooklyn Nine-Nine as well as my own position within these concepts. It is argued that fandom is potentially a very loose term and that it has no positive impact on the industry however, it is perhaps more arguable that fandom has nothing but a positive impact on both consumers and the industry. Additionally, the term fandom being broad and grey allows “everyone to have a fandom” (Rogers-Whitehead, 2016), which again can only have positive outcomes.

Similarly, it is also argued by many that textual poaching has little to no benefit on the industry and is nothing more than a display of “prolific amateurs” (De Kosnkik, 2012). However, I’d argue, after completing this research, that textual poaching surrounding Brooklyn Nine-Nine benefit: consumers, social media and the television industry as a whole.

I would be fascinated however; in finding out what other fans of my age would think about the discussed topics and which concepts they are a part of.

Bibliography

- Barb (2019) Top programmes report: week 18 April 29 – May 05. Available from: https://www.thinkbox.tv/Research/Barb-data/Top-programmes-report?tag=Adults1624 [Accessed: 18th May 2019]

- Battisby A, Avocado Social (2019) The latest UK social media statistics for 2019. Available from: https://www.avocadosocial.com/latest-social-media-statistics-and-demographics-for-the-uk-in-2019/ [Accessed: 18th May 2019]

- Blake, A (2018) how do people not love brooklyn nine nine. Availavle from: https://twitter.com/lisha_ronee/status/1129947462142181376?s=21 [Accessed: 20th May 2019]

- Blumler E, Katz J (1974) Uses and gratifications research. The public opinion quarterly. Oxford University press, UK.

- Brooklyn Nine-Nine (2013) Hot damn! The official twitter for #Brooklyn99, Thursdays at 9/8c on NBC! Available from: https://twitter.com/nbcbrooklyn99 [Accessed: 20th May 2019]

- Canlas K (2018) Fan of Brooklyn 99? Here are the funniest memes about the ‘Nine-Nine!’ Available from: https://www.wheninmanila.com/fan-of-brooklyn-99-here-are-the-funniest-memes-about-the-nine-nine/ [Accessed: 20th May 2019]

- Coppa F (2013) Fuck yeah, fandom is beautiful. The journal of fandom studies 2nd edition. Intellect, Muhlenberg College, USA.

- De Kosnik A (2012) Fandom as free labour. Digital Labour. Routledge, UK.

- Fiske J (1992) The cultural economy of fandom. The adoring audience: Fan culture and popular media. Routledge, UK

- Fregene, S (2018) Why Brooklyn Nine Nine is One of The Best Shows on TV. Available from: https://youtu.be/DTj5WV29oxo [Accessed: 20th May 2019]

- Gauntlett D (2008) Media, Gender and Identity: An Introduction 2nd edition. Routledge USA.

- Grossberg L (1992) Is there a fan in the house? The affective sensibility of fandom. The adoring audience: Fan culture and popular media. Routledge, UK.

- Hibberd J Entertainment Weekly (2019) Brooklyn Nine-Nine gets biggest ratings in 2 years after NBC move. Available from: https://www.google.com/amp/s/amp.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2018/may/14/brooklyn-nine-nine-fan-power-cancelled-nbc-fox [Accessed: 17th May 2019]

- Holt Soundboard. Available from: https://holt-soundboard.github.io/ [Accessed: 20th May 2019]

- Ibrus I, Scolari C (2012) Crossmedia Innovations: Texts, Markets, Institutions. Peter Lang AG, UK.

- Jenkins H (1992) Textual Poachers. Routledge, USA.

- Keyes E, The Yale Herald (2018) Brooklyn Nine-Nine: A Love Story. Available from: https://yaleherald.com/brooklyn-nine-nine-a-love-story-34bc80a0e6b [Accessed: 20th May 2019]

- laura does exams (2018) Me during cancellation period:. Available from: https://twitter.com/babydynamos/status/995144504721063936?s=21 [Accessed: 20th May 2019]

- Newbury C Hootsuite (2019) 130+ Social Media Statistics that Matter to Marketers in 2019. Available from: https://blog.hootsuite.com/social-media-statistics-for-social-media-managers/ [Accessed: 18th May 2019]

- Rogers-Whitehead C, Tedx Talks (2016) What’s Your Fandom? | Carrie Rogers-Whitehead | TEDxSaltLakeCity. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z3PWticpgd0 [Accessed: 16th May 2019]

- Shifman L (2012) An anatomy of a YouTube meme. New media & society. Sage Publishers, USA.

- TheWrap (2018) ‘Brooklyn Nine-Nine’ Saved by @NBC 1 Day After @FoxTV Cancellation. Available from: https://twitter.com/thewrap/status/995153511871463424?s=21 [Accessed: 20th May 2019]

- Tosenberger C (2011) Textual Poachers. Encyclopaedia of consumer culture. Sage Publications, USA.

- Williams R (2015) Post-object fandom: Television, identity and self-narrative. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, UK.